Why are more women saying no to having kids?, with Peggy O’Donnell Heffington (Ep. 142)

The Changing Landscape of Motherhood: A Historical Perspective on Declining Fertility Rates

As more and more women in the United States choose to forgo motherhood, the nation's fertility rate has reached its lowest point on record. This shift, however, is not a new phenomenon, nor is it solely the product of the modern feminist movement. For centuries, women have been actively making decisions about limiting births and opting out of parenthood altogether. A new book, "Without Children: The Long History of Not Being a Mother," by University of Chicago scholar Peggy O'Donnell Heffington, explores the historical trends and modern factors shaping this evolving landscape of non-motherhood.Uncovering the Roots of a Changing Narrative

The Fertility Transition: A Profound Shift in the Past

Contrary to popular belief, the concept of non-motherhood is not a recent development. In fact, Heffington's research reveals that fertility rates have been declining for over a century, with a dramatic drop observed in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars. Across Western Europe and the United States, the fertility rate plummeted, with women transitioning from having an average of seven births per woman to just three and a half by the turn of the 20th century.This "fertility transition" was driven by a confluence of factors, including the Industrial Revolution, which fundamentally altered the way people lived and organized their families. As the population shifted from rural to urban areas, the economic realities of raising a large family in a city made smaller household sizes more practical.A Parallel in History: Echoes of the Past in the Present

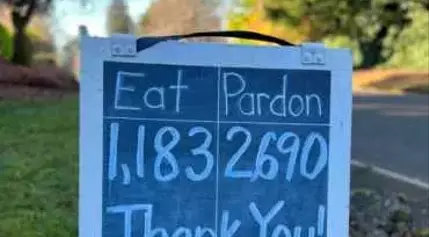

Interestingly, the current climate surrounding declining fertility rates bears a striking resemblance to a period over a century ago. Just as today, the early 20th century was marked by a global pandemic, economic uncertainty, and a widespread decline in birth rates. Women born between 1900 and 1910, who were coming of age during this tumultuous time, have the highest level of childlessness in American history, a distinction that may soon be surpassed by millennials.During the Great Depression, it's estimated that between one in every two and one in every three pregnancies were terminated, despite the fact that abortion was illegal at the federal level. This underscores the lengths women were willing to go to control their fertility in the face of challenging economic circumstances.The Comstock Act: A Forgotten but Lingering Threat

As the fertility rate declined, efforts to increase it emerged, including the implementation of the Comstock Act, which made it a federal crime to transport anything related to sex or contraception through the mail. This effectively banned access to contraception, a policy that remained in place until the Supreme Court rulings in Griswold v. Connecticut and Eisenstadt v. Baird in the 1960s and 1970s.Surprisingly, the Comstock Act has resurfaced in recent years, as anti-abortion groups have attempted to use it to limit access to abortions and contraception in states where they are still legal. This demonstrates the persistent and evolving nature of the debate surrounding reproductive rights and the control of fertility.The Workplace Barrier: Employers' Role in Shaping Motherhood

The private sector also played a significant role in reinforcing the expectation of motherhood. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it became commonplace for employers to implement "marriage bars," which required women to be fired upon getting married, as they were now expected to assume their "real role" as wives and mothers.Even in the post-World War II era, when the idealized image of the stay-at-home mom was widespread, the reality was quite different. Historian Stephanie Coontz found that even during this period, two-thirds of families had both parents working outside the home, as the economic demands of supporting a family often necessitated dual incomes.The Shifting Family Structure: From Community to Isolation

Heffington's research also reveals a profound shift in the structure of the American family, moving from a more collaborative, community-based model to the modern nuclear family. In colonial America, the family was deeply embedded within the larger community, with children frequently moving between households and women collectively supporting each other in the process of raising the next generation.However, as families began to move further from their extended networks, the burden of childcare fell squarely on the shoulders of mothers, who were now isolated within their nuclear family units. This transition, Heffington argues, had significant consequences for all women, regardless of their reproductive status, as they were suddenly shut out of the collective experience of nurturing the community's children.The Untapped Potential of Supportive Policies

Heffington's research suggests that the decline in fertility rates is not solely driven by economic pressures, as evidenced by the higher fertility rates observed in countries with more generous family-friendly policies. In France and Scandinavia, for example, where paid maternity leave, subsidized childcare, and healthcare are more readily available, fertility rates are higher than in the United States.Interestingly, these supportive policies not only enable parents to have more children but also contribute to their overall happiness. Studies have shown that in the US, there is a "happiness gap" between parents and non-parents, with the latter reporting higher levels of happiness. However, in countries with robust family support systems, this gap disappears, and parents are often significantly happier than their childless counterparts.These findings underscore the potential for policy interventions to create an environment that empowers individuals to make meaningful choices about parenthood, without sacrificing their personal well-being. As Heffington argues, the goal should be to "create policies that allow people to have as many children as they want, not policies that force people to have children they don't want."